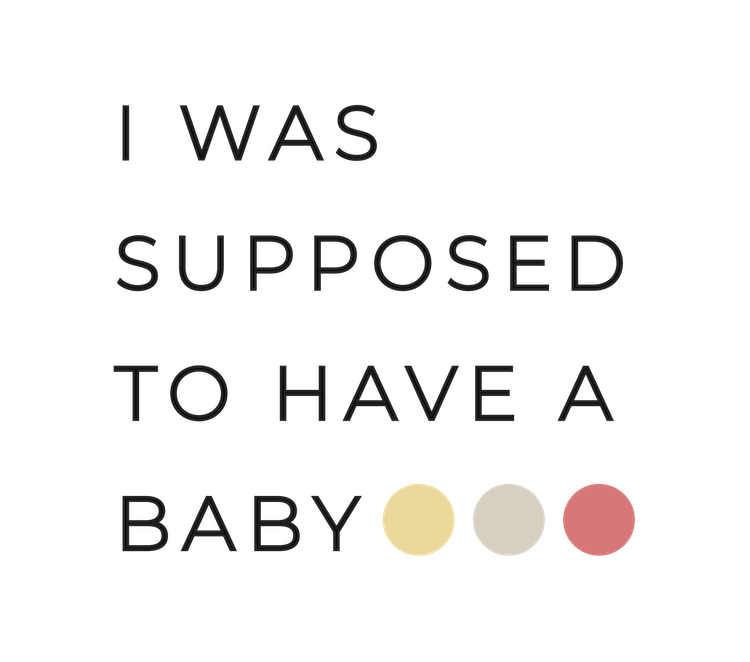

A Eulogy for a Person Who Never Got to Be

A Eulogy for a Person Who Never Got to Be by Rachel Rosenthal

“On the first Friday in January, I lay on a hospital bed in an operating theater on the 9th floor of an office building in Midtown. Dressed in two hospital gowns, a hair net, and socks with sticky bottoms, I saw our embryo appear on a giant screen. That embryo had been hard fought, the only normal one to come out of our third IVF retrieval more than six weeks earlier. It was the first male embryo we’ve ever created, after producing 8 females. We nicknamed him Schrodie, after Schrodinger and his famous cat—we were deeply aware of his precarity, hovering between the fulfillment of our dreams after months of treatment and another heartbreak. I watched him flashing on the screen as the embryologist transferred him into a tiny tube, and then on the sonogram machine right next to me, where he was carefully inserted into my uterus by my doctor. They gave me a picture of him, just a tiny bundle of cells who might become a person, to take home with me.

On the first Friday in February, I was back in the same office building, one floor above where I had first seen Schrodie on the screen. This time, I was wearing sweats and I was on an exam table. The same doctor who had deposited Schrodie into my body was now inserting four pills of misoprostol, one after the other, to induce an abortion. Schrodie, who had given us a positive pregnancy test, who I had seen just 10 days earlier flashing on the ultrasound, was not developing properly. Despite being pre-screened, he had a chromosomal abnormality and had stopped growing. However, my body hadn’t gotten the message that my pregnancy wasn’t viable. Instead, I was still throwing up, still having food aversions to everything but salty carbs, still covered in a blanket of fatigue. So my doctor inserted the pills to tell my body to let Schrodie go. One, two, three, four. A tiny pinch to remove what a tiny pinch had created. Within a few hours, I would be bleeding heavily, and then Schrodie would be gone.

On my second date with my now-husband, I turned to him on a crowded downtown subway and said, “Listen, if you want to have seven children, we probably shouldn’t go out again.”

This comment wasn’t as out of left field as it might have seemed. He is the oldest of seven and after only a few hours together, it was already clear how bonded he felt to his siblings. But I had four years on him in age, and I still needed to finish my dissertation. Plus, I couldn’t imagine fitting seven children in a Manhattan apartment. Seven children would be a dealbreaker.

I’ve been thinking about that moment lately, and the lightness of the comment born out of my naivete. I was so sure, at the time, that I would be in control of the number of children I would have. Just as I couldn’t imagine seven children, I couldn’t have imagined seven pregnancies. But as it turns out, Schrodie was my seventh pregnancy, and my sixth loss. We are incredibly blessed to have our miraculous daughter, E, who we love more than we knew was possible, and who came after the first three of those losses. We feel deeply grateful for her, and also deeply sure that our family does not feel complete. However, with each passing day, with each IVF cycle, with each negative pregnancy test, with each chemical pregnancy or miscarriage, I am more and more aware that the choice to add more children to our little family might not be up to us after all. We have so much more than we could have hoped for, and yet, we aren’t satisfied. I feel ashamed of my greed, of my desire for more, and also feel deeply justified in my anger at not being able to have what I want. I want to be a mother to more children. I want to see my husband holding hands with our tiny infant while they lie on the bed together. I want to see E, who is increasingly interested in babies, get to be a big sister. I want, I want, I want.

I can count all of the ways in which I am lucky. I am lucky to have E, who heals some of the cracks in my heart every time she laughs or comes over just to hug me, before continuing on her way. I am lucky to have a partner who loves and supports me unconditionally. I am lucky to have the resources to pursue fertility treatment. I am lucky to live in a state where I have access to abortion pills, and to a pharmacy where the pharmacist did not refuse to fill my prescription. I am lucky to have access to healthcare, which is tragically not a given in this country. I am lucky to have a loving and supportive family, and colleagues and students who encouraged me to take time to heal physically and emotionally after I lost Schrodie. Lucky, lucky, lucky, lucky. And yet, I want.

One of the strange things about mourning a miscarriage is that it is often invisible. There’s no ritual for it. There’s no funeral, no shiva, no kaddish, no yahrzeit. None of these would feel right away. Schrodie wasn’t a baby, he wasn’t a person. He was only the possibility of one. And yet, he is the first thing I think of when I wake up in the morning, and the loss of him is with me just as his presence was with me for those four short weeks. If the other five pregnancies I have lost are any indication, his mark on me will remain long after the bruises from the shots and blood draws that dot my arms, stomach, and back fade. Schrodie would have been due on Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish year. He will not be there, and yet, he will be with me. I will be in shul without him but with him, aware of what isn’t and what could have been.

Last Saturday night, after having spent all day in bed bleeding, cramping, and crying, I went into E’s room to check on her while she slept. I do this almost every night, both to make sure she’s sleeping well, and also because seeing her in deep sleep is like a balm to my soul. That night, her hand was sticking out of the side of her crib, like she knew I needed her. So I sat next to her crib and I held her hand and I cried. And as my tears fell, I felt her grip, ever so slightly, tighten around my finger, even as she continued to breathe deeply. I felt in that moment, impossibly, my heart both break and heal.

There’s no happy ending here, at least not yet. There’s no lessons or words of Torah to replace what we have lost. I wish I had words to tie this story up in a neat ending, but life too often doesn’t work that way. I will feel grateful for E and I will mourn Schrodie and I will take comfort in the people who love me, and in the little family my husband and I have created. Hopefully, at least for today, that can be enough.”